01/25/2015 13 157 4 Reading time: 10 min. Rating:

Author

: Konstantin Bely

Today I will tell you about what quantitative easing (QE) , why quantitative easing programs , how they work, and what results they lead to. You've probably heard or read a lot about such programs in the news in recent years. Already 3 QE programs have been implemented in the United States, and most recently the first quantitative easing program was adopted in the eurozone countries, the implementation of which will begin in March 2015. What it is, how it affects the country implementing the program, and how it can affect the economy of our countries - you will learn about this by reading this article. I will try to explain as clearly as possible, in simple and understandable language.

Introduction to Basics

Most of the money in our economy is created by banks when they make loans. But after the financial crisis, banks stopped lending and stopped creating new money.

At the same time, people were still paying off their loans, which meant that money was being "destroyed" and the total amount of money in the economy was shrinking. To counter this and "replace" the money that was destroying the banks, for example, the Bank of England created £445 billion of new money through a scheme called Quantitative Easing (QE). As the then Governor of the Bank of England said:

“A damaged banking system means that banks today are not creating enough money. We have to do this for them."

— Sir Marvin King, then governor of the Bank of England, spoke in 2012.

Notes[edit | edit code]

- ↑ Quantitative Easing Explained (undefined). — London: Bank of England, 2011.. — “The MPC's decision to inject money directly into the economy does not involve printing more banknotes. Instead, the Bank buys assets from private sector institutions - that could be insurance companies, pension funds, banks or non-financial firms - and credits the seller's bank account." Archived copy (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Access date: September 25, 2011. Archived October 30, 2010. - ↑ Quantitative Easing (undefined)

. Bank of England. — “The Bank can create new money electronically by increasing the balance on a reserve account. So when the Bank purchases an asset from a bank, for example, it simply credits that bank's reserve account with the additional funds. This generates an expansion in the supply of central bank money." Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. - ↑ 1 2

Q&A: Quantitative easing,

BBC

(9 March 2009). Retrieved March 29, 2009. - ↑ 1 2

Quantitative Easing Explained

(unspecified)

(unavailable link). Bank of England. — “This does not involve printing more banknotes. Instead the Bank pays for these assets by creating money electronically and crediting the accounts of the companies it bought the assets from." Archived March 16, 2009. - ↑ Elliott, Larry

. Guardian Business Glossary: Quantitative Easing, London: The Guardian (8 January 2009). Retrieved January 19, 2009. - ↑ Sterling Monetary Framework Operational Standing Facilities (unspecified)

(unavailable link). Access date: September 25, 2011. Archived November 13, 2011. - ↑ ECB Standing facilities

- ↑ Open market operations: A Glossary of Political Economy Terms - Dr. Paul M. Johnson

- ↑ 12

Open Market Operation - Fedpoints - Federal Reserve Bank of New York - ↑ Swiss National Bank: Monetary policy Instruments

- ↑ 12

The implementation of monetary policy in the euro area. - European Central Bank, 2008. - P. 14-19. - ↑ Dr. Econ: I noticed that banks have dramatically increased their excess reserve holdings. Is this buildup of reserves related to monetary policy? (undefined)

. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (March 2010). Access date: April 4, 2011. Archived August 29, 2012. - ↑ Bernanke, Ben

The Crisis and the Policy Response

(unspecified)

. Federal Reserve (January 13, 2009). Access date: April 4, 2011. Archived June 7, 2012. - ↑ 1 2 Bowlby, Chris

. The fear of printing too much money, BBC News (5 March 2009). Retrieved June 25, 2011. - ↑ Isidore, Chris

. Federal Reserve move toward quantitative easing poses risks, CNNMoney.com (October 5, 2010). Retrieved June 25, 2011. - ↑ Abel, Andrew & Bernanke, Ben (2005), 14.1, Macroeconomics

(5th ed.), Pearson, p. 522–532 - ↑ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2002), Chapter 18: Money Supply and Money Demand, Macroeconomics

(5th ed.), Worth, p. 482–489 - ↑ Eggertsson, Gauti

. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Archived November 22, 2011. - ↑ What is the optimal inflation rate?.

- ↑ Bullard, James

Quantitative easing—uncharted waters for monetary policy

(undefined)

. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (January 2010). Access date: July 26, 2011. Archived August 29, 2012. - ↑ Quantitative Easing explained (undefined). - Bank of England. — P. 7-9. - ISBN 1857301145.. - “Bank buys assets from ... institutions ... credits the seller's bank account. So the seller has more money in their bank account, while their bank holds a corresponding claim against the Bank of England (known as reserves … high-quality debt … such as shares or company bonds. That will push up the prices of those assets… ". Archived copy (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Date of access: September 25, 2011. Archived October 30, 2010. - ↑ Quantitative easing: A therapy of last resort, The New York Times (January 1, 2009). Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Heather

. Quantitative easing: last resort to get credit moving again, London: The Guardian (29 January 2009). Retrieved July 12, 2010. - ↑ Ivan Tkachev.

Trillions out of thin air: the Fed has curtailed the historic QE program (Russian). Rbc.Ru (October 30, 2014). Access date: November 11, 2014. - ↑ Protocol on the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank: statements 14.4, 18.2 (unspecified)

5–6. Access date: April 7, 2011. Archived August 29, 2012. - ↑ Unconventional Choices for Unconventional Times: Credit and Quantitative Easing in Advanced Economies

- ↑ Feldstein, Martin

Quantitative Easing and America's Economic Rebound

(unspecified)

.

project-syndicate.org

. Project Syndicate (February 24, 2011). Access date: April 4, 2011. Archived August 29, 2012. - ↑ Thornton, Daniel

L. The downside of quantitative easing. - ↑ Inman, Phillip

.

How the world paid the hidden cost of America's quantitative easing, The Guardian

(29 June 2011). - ↑ Bernanke's `Cheap Money' Stimulus Spurs Corporate Investment Outside US - Bloomberg

How does quantitative easing work?

QE has generally been portrayed in the press as "The Bank of England prints money and lends it to banks so they can increase lending in the economy", but this is completely inaccurate.

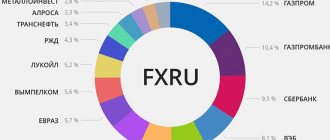

In effect, through QE, the Bank of England was buying financial assets - almost exclusively government bonds - from pension funds and insurance companies. He paid for those bonds by creating new central bank reserves, a type of money that banks use to pay each other.

The pension funds will sell the bonds to the Bank of England, and in return they will receive deposits (money) in an account at one of the major banks, RBS said. As a result, RBS will receive a new deposit (a liability from it to the pension fund) and a new asset - central bank reserves at the Bank of England.

Therefore, the easing simultaneously increased a) the amount of central bank money that is used in the system that banks use to pay each other, and b) the amount of commercial bank money (deposits in the bank accounts of people and companies). Only real deposits can be spent in the real economy, as central bank reserves are only for internal use between banks and the Bank of England.

Why has easing been ineffective in boosting GDP?

The problem was that the money created through QE was used to buy government bonds in the financial markets (pension funds and insurance companies). Thus, the newly created money flowed directly into the financial markets, raising the bond and stock markets to near the highest levels in history. The Bank of England itself estimates that QE has increased bond and share prices by around 20% ( source ).

In theory, this should make people feel richer so they will spend more. However, 40% of the stock market is owned by the richest 5% of the population, so while most households have not seen the benefit of QE, the richest 5% of households would have had up to £128,000 at best.

Very little of the money created by QE contributed to the growth of the real (non-financial) economy. The Bank of England estimates that the first £375bn of QE resulted in GDP growth of 1.5-2%. In other words, £375 billion of new money is required through QE just to create £23-28 billion of extra spending in the real economy. This is incredibly ineffective because it relies on increasing the wealth of the already rich and hopes that they will increase their spending. In other words, it relies on a “rich” theory of wealth.

A much more effective way for the Bank of England to stimulate the economy would be to create money, provide it directly to the government, and allow the government to spend it directly in the real economy. This is exactly the approach we advocated in our Sovereign Money: Charting the Path to a Sustainable Recovery article, and on a per-pound basis of stimulus it would be many times more effective than quantitative easing.

The whole idea is to keep as much money circulating in the economy as possible. It's like giving the economy an adrenaline rush.

Monetary policy is a macroeconomic policy implemented by a country's central bank to control the money supply and interest rates in the economy.

- Expansive monetary policy is when the central bank tries to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates and increasing the money supply.

- Contractionary monetary policy is when the central bank tries to cool the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the money supply.

- Standard monetary policy would be to lower interest rates to stimulate investment and consumption, leading to economic growth.

However, this type of monetary policy has its limits. What happens when interest rates are at or near zero and the economy is still struggling? What should the central bank do?

In this case, central banks may consider quantitative easing.

Quantitative easing (QE)

Quantitative easing, also called “QE,” essentially refers to a more extreme monetary policy in which the central bank buys government bonds from banks and other financial institutions.

The idea is that buying government bonds from banks will increase the supply of money in the economy. Banks held bonds, now they hold money.

The central bank's hope is that banks take this pile of money and lend it to businesses and consumers. In theory, this will increase liquidity and investment in the economy and stimulate economic growth.

Economics tells us that when we increase the supply of any good, it decreases the cost. Money is no different. Increasing the money supply will make money "cheap" and by that I mean banks can lend money at a lower rate and with fewer terms.

The whole idea is to keep as much money circulating in the economy as possible. It's like giving the economy an adrenaline rush.

Example of correct use of Quantitative Easing

Let's simulate an economic situation in which quantitative easing will be necessary. Let's imagine that the central bank is making every effort to keep inflation at the desired level. And moderate inflation, as is known, is an indicator of a healthy, developing economy, while deflation is a sign of stagnation.

The actions of the Central Bank do not lead to results - there is no growth in the economy and prices. Companies and private consumers do not feel confident in the future, so they are in no hurry to take out loans. Thus, the multiplication (increase) of money is suspended.

Due to the economic crisis, the state is cutting its expenses, which slows down business development. The number of jobs is also declining, so the population’s demand for services and goods is falling.

With less money left over, people are increasingly turning to their banks to withdraw their deposits. And trust in financial institutions is also falling.

The logic of the average investor is as follows:

“It’s better to keep your savings under your pillow; although they won’t bring in income, they certainly won’t be lost if the bank goes bankrupt.”

And banks are experiencing an even greater liquidity shortage.

If the central bank can no longer reduce the interest rate, then it enters into a mutually beneficial deal with commercial banks.

And if you imagine it as a dialogue, it would look something like this:

Banks:

“We have catastrophically little money, we are facing a series of bankruptcies, which will obviously be followed by a powerful economic collapse in the country.” Panic is growing in the market, what to do?

Central Bank:

— Do you need free money? I am ready to provide them to you. But you understand, I just can’t do this. But I can buy your assets.

Banks:

- Yes, we have bonds, debt obligations on which we should receive interest in a few years. But, alas, now they are a useless burden, and we are ready to get rid of them in exchange for cash liquidity.

Of course, the central bank does not buy all the securities at once; that would be too risky. The mitigation program lasts several months and even years. The ransom amount may increase or decrease depending on changes in economic conditions. But the main thing is that the economy receives money and can use it to revive it. Production is picking up again, people are getting jobs, consumer demand is growing, which means we can expect GDP growth. And all this thanks to the QE program.

What are the disadvantages of QE?

The QE policy has two main disadvantages.

- Potential for inflation (or worse, stagflation).

- Devaluation of the national currency.

There is a possibility that an increase in the money supply and an excessive reduction in interest rates will lead to increased inflation. Since the mandate of many central banks is to contain inflation, this is a bit difficult.

In the worst case, the QE policy will fail to stimulate the economy and increase inflation. This can lead to stagflation, where the economy contracts and prices of everyday goods rise. Stagflation is very painful for an economy and the people who live in it.

Another disadvantage of QE is that it devalues countries' currencies. This can be beneficial for exporting companies as it will make their products more competitive in international markets.

For the general consumer though this is bad. A lower national currency means that the prices of imported goods will rise and people's purchasing power will fall.

The advantage of the system is simplicity, the disadvantage is that it doesn’t work very well.

As one of the canons of “Economic Theory”, dating back about two hundred years, says, the primary tool for managing the economy for monetary authorities is the interest rate. By changing its size, the regulator makes money cheap or expensive. But when the money supply reaches trillions of monetary units, interest rates fall to below 1% per annum.

There was a lot of money, but it no longer fulfilled the function of accelerating production and satisfying consumer needs. The classical money market, described in canonical textbooks, simply ceased to exist with the failure of the interest rate instrument.

As a matter of fact, the operation of the money machine in the “7 days a week” mode has always been considered by the monetary authorities as a gross abuse of power and almost a crime.

An oversupply of money supply causes inflationary rises in prices, disruption of economic equilibrium, neutralizes the stimulation of productive labor and increases social and property disunity.

Does quantitative easing work?

The effectiveness of QE policies has been the subject of some debate. Many economists believe that the QE policy after the 2008 financial crisis saved the United States and possibly the global economy.

On the other hand, many argue that the scale of the QE policy in 2008 was too extreme. The Federal Reserve bought $4 trillion in government bonds and distressed assets from banks on the brink of collapse. The idea, of course, was that the banks would then take that $4 trillion and lend it to people and businesses. While the QE policy kept banks from falling and increased the money supply, many banks simply sat on that money.

At their peak, US banks used more than $2.7 trillion in excess cash reserves. That's $2.7 trillion that is essentially sitting on the sidelines, doing nothing, when it could (and perhaps should) be circulating through the economy.

One of the biggest criticisms of CC policies after the financial crisis was that there was no mechanism in place to force banks to lend money to struggling consumers and businesses.

Low borrowing costs encourage more spending and boost the economy

When borrowing costs fall, consumers and businesses borrow more money and buy more goods. The following very simple example explains how this works.

If borrowing costs fall, people naturally borrow more money and spend it, which stimulates the economy.

For example, the more trucks you have in your transport business, the more you can expand the company. You decide to take out a loan of $20,000 to buy a truck, with payments of $250 per month. If the cost of borrowing drops by half, then you can now borrow $40,000 and buy two trucks for the same cost of $250 a month, and you'll likely buy two trucks and expand your business even more.