Ray Dalio

After the coronavirus made its way to Europe and the United States, global markets are literally in a fever. The indices of almost all European, Asian and American stock exchanges have already experienced several falls, and it is not yet known how long this situation will continue.

Along with the others, the world's largest fund, Bridgewater Associate, founded by Ray Dalio, also suffered significantly. How much did the hedge fund sink, why did it fall into the red zone if Dalio foresaw the crisis two years ago and why is Bridgewater betting on the fall of the markets?

- The largest hedge fund contracted the coronavirus

- Short Game

- Dalio's Apocalyptic Prophecies

The largest hedge fund contracted the coronavirus

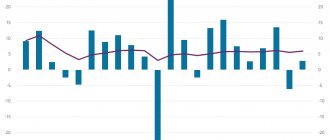

The fall of Bridgewater Associate amid the coronavirus

Bridgewater Associate is the world's largest hedge fund with more than $160 billion

. The company operates in 150 markets around the world, and its clients include large institutional investors, pension funds and even government agencies. The founder of the fund, Ray Dalio, with a personal capital of $18 billion, occupies a modest 46th place in the Forbes billionaire ranking.

☝️

Bridgewater is considered a pioneer in risk parity trading, and the company's trading strategy, Global marco, is based on analyzing a huge amount of data and maximizing portfolio diversification.

It is known that the fund employs more than 1,700 employees, and computational algorithms are used to analyze information arrays, as Dalio himself spoke about. Actually, that’s why in 2008, when the stock index fell by more than 30% and most companies closed the year with a fat minus, Bridgewater added 9.5% to its capital.

However, 2020 does not appear to be much like 2008. Thus, on March 18, WJS published data from a notice to investors on LinkedIn, according to which the company’s main fund, Pure Alpha, where almost half of the funds are accumulated, has dropped by 20% since the beginning of the year. And more precisely, for all funds, then:

- All Weather (10% share) lost 12%;

- All Weather (12% share) lost 14%;

- All Weather China RMB lost 9%;

- Pure Alpha (12% share) lost 14%;

- Pure Alpha (18% share) lost 21%;

- Pure Alpha Major Markets share (14%) lost 7%;

- Pure Alpha Major Markets (21% share) lost 11%;

- Optimal Portfolio (10% share) lost 18%.

Dalio added that "the situation is not what we would like, but it is what should be expected under the circumstances."

However, he also noted that Bridgewater, although it was committed to economic growth in 2020, also insured itself in case of a market decline, and all the company’s compensating and balancing mechanisms work as intended. Bridgewater remains solvent and can continue to operate.

And in general, you can believe this, because the losses of the hedge fund against the backdrop of a general fall in the stock index (16% as of March 18) do not look that big.

Extreme transparency and absolute honesty in personnel assessment

Bridgewater uses the principles of radical truth and radical transparency introduced by Ray Dalio to evaluate personnel. In practice, these principles are implemented using Dots, a special iPad application that allows for real-time assessment.

Dots personnel assessment application. YouTube/TED

Each employee of the company has this application on his tablet and evaluates other employees with whom he has to interact, more than 100 criteria, using a 10-point scale.2

“My goal has been to do meaningful work and have meaningful relationships with the people I work with. And I realized that they are impossible without extreme transparency and algorithmic decision making,” explains Ray Dalio. Some aspects of this assessment may seem shocking, he admits.2

Short Game

Bear Market 2020

Bridgewater attempted to protect its position in a falling market by placing a total of $14 billion in bear orders on European markets. The company made a series of bets in EU countries, including Germany and Italy, and these bets appear to have indeed been profitable.

Bridgewater Associate, commenting on the situation, noted that the company trades around the world and calculates its operations taking into account risk parity, so it would simply be incorrect to evaluate rates in the EU separately from other transactions.

It is noteworthy that back in November 2019, The Wall Street Journal, citing “people familiar with the situation,” published material that Bridgewater was betting on the fall of the European market until the spring of 2020. True, the amount there was more modest - $1.5 billion. Commenting on the news, Dalio denied betting on a fall and accused WJS of publishing false information and “hunting for sensations.”

Although this is not the first time for Bridgewater to make money on a market decline. In February 2018, the fund also bet on the fall of European companies (Italian, German and British) amounting to $14 billion. And this produced results - a 14.6% return while the entire market was in the red zone.

Therefore, the bearish sentiment in March may indeed be part of Bridgewater's global strategy to diversify risks, moreover, it is quite justified and appears to have helped mitigate the shocks of March. We can only guess how much of the total fund the company would have lost without these offsetting transactions.

Bridgewater Associates: financial markets as a social system

The world's largest hedge fund management company, Bridgewater Associates, with assets worth $94 billion. The head of the management company is Ray Dalio. This man is so unusual in the world of finance that he is rarely called an “economist.” The company refers to him as a “mentor”, fans of his theories call Dalio a “philosopher”, and ill-wishers openly talk about the founder and head of Bridgewater as a sectarian who cruelly mocks staff and fools young people with fragile brains.

What ill-wishers say

The financial market is saying strange things about both Dalio himself and Bridgewater, which he created. Particularly suspicious, according to general opinion, is the fact that the company keeps to itself. Its headquarters are located far from Wall Street, in the deep woods of Connecticut, around an inconspicuous turn with no signs. Its leader is “too” charismatic and too fond of preaching his ideas to employees, demanding unconditional obedience from them.

Some haters even compare Dalio to Mao Zedong, and his foundation and the principles of work in it to utopias from the books of Ayn Rand or Deepak Chopra. In general, they whisper on Wall Street - if life and sanity are important to you, do not go to work at Bridgewater, especially since bonuses there are on average slightly lower than at Goldman Sachs and similar companies, and crazy corporate parties do not happen more often than once a quarter.

Management at Bridgewater is indeed quite different from Wall Street management. The fund buys and sells hundreds of different instruments every day from a wide variety of countries, from Japanese bonds to copper futures and exotic currencies like the Brazilian real. But unlike his fellow managers, Dalio does not sit in front of a monitor for days on end, does not track trends, and generally does not particularly like the volatile and unpredictable stock market (although he started with it at the age of 12), preferring the currency and bond markets. The reason is simple. When buying and selling securities, Bridgewater relies no longer on inside information or trading robots, but on intelligence - its own “philosophy” and the depth of the economic analysis it applies.

In this regard, the financial markets in this regard are considered by Bridgewater management as a social system, with the only difference that the “rewards” and “punishments” in it are expressed in numbers on the account, while the main goal is to understand how the economy works and what causes “breakdowns” ", and the difference between Bridgewater and many stock speculators is that it almost always plays not on immediate, but on large macroeconomic trends.

As for economic cycles, it is quite possible to calculate them based on global economic and political indicators - for example, changes in LIBOR or an increase in the size of the national debt. A modern computer will allow you to process changes in many indicators, compare the situation with what has already happened in the economy before, and predict further developments.

Financial ecosystem

A “systemic” approach focused on macroeconomic trends works well in Bridgewater: over the entire period (since 1991), the fund has shown losses only for three years, and on average shows a profit of 18% per year. Nearly all of Bridgewater's financial market peers posted losses in the recessionary year of 2008, but its flagship fund, Pure Alpha, posted an impressive 9.5% gain. 2010 produced a crazy profit of 45%, which was the best figure in the industry and brought Bridgewater into first place in terms of the amount of capital allocated to it for management.

Bridgewater likes to emphasize how much the financial market is like an ecosystem. For example, hunting wild animals is often compared to investing: in both activities, it is important to “control risks” and “keep the right distance from danger.”

In trading on the market, this can be done, for example, by distributing risks: the Pure Alpha fund always has at least 30-40 positions in different securities in its portfolio and does not concentrate capital in any of the instruments, unlike Soros or the famous John Paulson , which played before the crisis exclusively against American mortgage securities. Bridgewater never focuses on just one thing, because today, markets are often too closely related to each other and rise or fall at the same time, which makes diversification difficult. Therefore, Bridgewater tries to diversify its portfolio as much as possible by making many “distributed” bets and simultaneously shorting and buying securities of the same class.

For example, a fund could buy platinum, believing that prices will rise further, and at the same time sell silver. Or buy thirty-year US bonds and sell ten-year bonds at the same time. At the beginning of this year, for example, Bridgewater actively shorted American securities, and these bets played out when the market stumbled in the middle of the year. Bets on some commodities and emerging market currencies played out similarly. Bottom line: While most hedge funds lost money, Pure Alpha gave investors a 10% return.

Bridgewater's "ecosystem" thinking has another consequence - the political views of its leader. He endorses capitalism, supports conservatives (and was even a donor to John McCain's presidential campaign), and is a Darwinian advocate of limiting government intervention in the economy. He believes that the strongest survive, and even the most efficient system will still work exactly as long as it is allotted, and then die. Perhaps this is why Bridgewater immediately withdrew its money from Lehman Brothers and other Wall Street companies as soon as the market smelled of frying.

“Transparency” of decisions or bullying of staff?

The essence of “transparency” is very simple. There is no hierarchy of opinion of any kind at Bridgewater. On the contrary: Bridgewater management encourages employees, even those who work in lower positions, to express their point of view on any issues at meetings (of course, this opinion must be reasoned) and not be afraid to argue with the most important experts and the most senior managers. Gossip behind your back is strictly prohibited. But any idea expressed and any action can be discussed, approved or ridiculed; there are no unshakable authorities.

At the same time, the company is allowed to criticize literally everything - from the food in the cafeteria to decisions about the purchase of specific papers and the bad habits of individual employees who, for example, forget to wash their hands after visiting the toilet. If criticism does not help, colleagues give the offender a serious debriefing in the style of the Spanish Inquisition. And woe to anyone who dares not comply with the collective directives prescribed at such a meeting.

How Bridgewater performed during the crisis

What is the secret of Bridgewater's success? Co-CEO Bob Prince attributes this to Bridgewater's combination of global thinking and street smarts. Most economists go top-down in their analysis: they take macroeconomic data and look at what it means for specific industries and companies, and buy or sell securities depending on this. Bridgewater does exactly the opposite. In each market that Bridgewater is interested in, it identifies groups of “players” - sellers and buyers, after which they try to understand how much and what they will buy and when, and depending on this, calculates which securities and raw materials will be in demand and which, on the contrary, they will be underestimated.

In relation to the US bond market, it works like this: Bridgewater carefully checks who participates in the weekly auctions held by the Treasury (US banks, foreign central banks, pension funds and other funds), and what they buy and what they don’t. And in the raw materials market, the share of demand on the part of companies and commodity speculators is studied - this helps to understand who, what and how much will sell and for what reason.

In addition, in each of the markets in which Bridgewater operates, there are dozens of different indicators that signal certain changes. All of them are entered into the database and help traders navigate even in not very well known areas. But, importantly in Bridgewater's case, if most or even all indicators point in the same direction (and give a clear buy or sell signal), the fund manager does not automatically make a decision, relying solely on the software.

Any investment decision must be approved by partners - head Ray Dario, co-executive directors of the fund Greg Jensen, who is only 36 years old, and the aforementioned Bob Prince. Of course, such a collegial method of decision-making makes Bridgewater's activities more dependent on the human factor. However, the management of the management company notes that the rules by which the fund operates were created over the past 30 years and, as they say, have been tested over the years, and every decision that was made was made taking into account the surrounding situation. And it is this commitment to the “system”, both in careful analysis and in investments, that sets the fund apart from the funds of its fellow competitors.

“When the fund considers the state of the economy as a whole, they pay special attention to the amount of credit (that is, those that they are able to issue on credit) money in banks and other financial institutions. Until recently, very few analysts prioritized this factor, preferring to focus on the amount of “real” money in the economy—cash, deposits, and so on.

Meanwhile, Bridgewater, based on the amount of borrowed funds, predicted a possible crisis in the mortgage securities market in the United States back in 2007. It was at this time that the fund's computers began to signal what Bridgewater called a "D-process" - a type of country default, exactly like the one that had broken out in the Weimar Republic in Germany. Having received the first alarming data, Bridgewater analysts scoured through open sources almost all the financial documentation available to them of the largest financial companies in the world and, in amazement, calculated that due to “bad” debts, these structures could lose $839 billion.

Armed with these calculations, Dalio went straight to the US Department of the Treasury (Treasury) in December 2007 and secured a meeting with the deputies of then-Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, and then tried to attract attention in the White House. Unfortunately, no one in any of the departments was interested in Bridgewater’s data at that moment.

Confession

At the beginning of 2008, the fund issued a memorandum in which it openly predicted that a financial crisis would soon break out, followed by a general economic crisis. But the document again attracted attention too late - after the recession began in America. It was then that Dalio acquired an ardent admirer in the White House - Lawrence Summers, who headed the National Economic Council in 2009-2010.

While America was dealing with the crisis, Pure Alpha and other Bridgewater funds were profiting from the chaos. The fund was well aware that the Fed would simply be forced to turn on the printing press in order to “pour” money into the economy, and predicted that despite all the efforts of the Barack Obama administration, growth would be small. Therefore, Bridgewater management instructed traders to play bearishly: go long on Treasury bonds, short the dollar and buy gold and other commodities.

The bearish strategy allowed Bridgewater to post a profit in 2008, although it later led to losses in 2009 because Dalio underestimated the speed of the industry's recovery. But in 2010, when growth slowed again, Bridgewater was back on top. Amid the ongoing stagnation, 80% of his bets worked, and the fund made huge profits against Treasury bonds and other government securities.

Today, Bridgewater is again betting on slowing growth in the US and Europe. Firstly, the measures proposed to overcome the crisis by the Barack Obama administration, in his opinion, will sooner or later cease to operate. Second, too many countries are saddled with debt burdens that are holding them back from developing. And third, he notes, China and other developing countries will soon have to take measures to curb inflation, which will also slow down their growth.

The recovery period, according to the head of Bridgewater, could drag on for ten years, if not more, and especially problems will be added when the United States turns on the printing press again to try to ease its debt burden: this could lead to a collapse in the government bond market and a fall in the national economy. currencies.

As for Europe, where the European Central Bank does not have the authority to print “extra” currency, this region, according to the forecast of the head of Bridgewater, will simply face a “classic” depression, and the end of 2012 - beginning of 2013 will be another difficult period in all markets.

How does this work in practice?

Dalio demonstrated how his company evaluates personnel at one of the TED conferences.

Ray Dalio. Flickr/TED Conference

All meetings at Bridgewater Associates are videotaped. Dalio showed one of these videos to conference participants.

During the Bridgewater meeting, everyone in attendance had the Dots app running on their tablet. Each of them has more than 100 characteristics at their disposal, by which they can evaluate the other participants. This includes, for example, work habits, discipline, the desire to develop and develop others, focus on results, etc.1,2

During the meeting, one of the participants felt that Ray Dalio did not meet the corporate standards he had set. She selected the “Confidence and Openness” characteristic on her iPad and gave the company leader a three out of ten on this indicator.

A colleague rated Dalio a 3 out of 10. YouTube/TED

She felt that Dalio did not make his points clearly enough and was not open enough in his reasoning. She added the corresponding comment to her assessment.

It should be noted here that Dalio himself claims that this is one of his favorite aspects of Bridgewater's corporate culture - any recent graduate working at the company can subject him to harsh criticism without fear of retribution. In general, criticism of management is even welcome if the situation requires it.

A participant who rated Dalio during a meeting does the same with several other colleagues. Each of them gets their own point. Another meeting participant thought Ray Dalio led the meeting well and gave him a nine out of ten. He provides an explanatory commentary to the assessment. All ratings and comments are displayed on the tablets of all those present.1, 2

Peer ratings with comments. YouTube/TED

This way, all participants will know in real time how the colleagues present at the meeting evaluate their participation in the meeting.

YouTube/TED

In addition, the Dots application can be used to collect opinions, conduct voting and make general decisions.1