Financial institutions try to attract the attention of customers by offering favorable interest rates on deposits. At first glance, the yield values are very attractive in a number of cases. Investing your savings at rates above 12% is currently an ultra-generous proposition. However, everyone sees the interest rate numbers in large, bright font, and few people read the text written in small font at the bottom. Banks declare only the nominal income that the depositor will receive after a specified period. They never mention the concept of “real income,” which is what the client actually receives. Let's take a closer look at what the nominal and real deposit rates are, how they differ, what are their similarities, and how to calculate real income?

Interest rate concept

The interest rate should be understood as the most important economic category that reflects the profitability of any asset in real terms. It is important to note that it is the interest rate that plays a decisive role in the process of making management decisions, because any economic entity is very interested in obtaining the maximum level of revenue at minimum costs in the course of its activities. In addition, each entrepreneur, as a rule, reacts to the dynamics of the interest rate in an individual way, because in this case the determining factor is the type of activity and the industry in which, for example, the production of a particular company is concentrated.

Thus, owners of capital assets often agree to work only if the interest rate is extremely high, and borrowers are likely to acquire capital only if the interest rate is low. The examples discussed are clear evidence that today it is very difficult to find equilibrium in the capital market.

See also[ | ]

- Interest income

- The cost of money taking into account the time factor

- Annual Percentage Yield

- Refinancing rate

- Discount rate

- Lombard rate

- European Interbank Offered Rate (EURIBOR)

- London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR)

- Interest capitalization

- Future Rate Agreement (FRA)

- Rule of seventy

- Inflation

- Compounding

- Compound interest

Interest rates and inflation

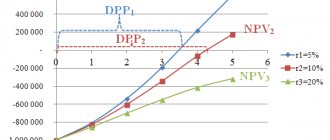

The most important characteristic of a market economy is the presence of inflation, which determines the classification of interest rates (and, naturally, the rate of return) into nominal and real. This allows you to fully assess the effectiveness of financial transactions. If the inflation rate exceeds the interest rate received by the investor on investments, the result of the corresponding operation will be negative. Of course, in terms of absolute value, his funds will increase significantly, that is, for example, he will have more money in rubles, but the purchasing power that is characteristic of them will drop significantly. This will lead to the opportunity to buy only a certain amount of goods (services) with the new amount, less than would have been possible before the start of this operation.

Results

Omitting details, I want to say that earning money on deposits is the safest type of investment , which in fact simply covers the inflation of money and serves to save large sums from devaluation. With the right approach, the contribution gives a good increase in the salary of an office worker. If you liked the article, subscribe to the blog and leave comments. Write everything you think under these lines.

If you find an error in the text, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter. Thanks for helping my blog get better!

Distinctive features of nominal and real rates

As it turned out, the nominal and real interest rates differ only in conditions of inflation or deflation. Inflation should be understood as a significant and sharp increase in prices, and deflation should be understood as a significant drop in prices. Thus, the nominal rate is the rate set by the bank, and the real interest rate is the purchasing power inherent in income and denoted as interest. In other words, the real interest rate can be defined as the nominal interest rate, which is adjusted for inflation.

Irving Fisher, an American economist, formed a hypothesis explaining how the level of real interest rates depends on nominal ones. The main idea of the Fisher effect (this is the name of the hypothesis) is that the nominal interest rate tends to change in such a way that the real one remains “stationary”: r(n) = r(p) + i. The first indicator of this formula reflects the nominal interest rate, the second - the real interest rate, and the third element is equal to the expected rate of inflation processes, expressed as a percentage.

Compensation for loan

A person who lends money to repay it at a later point in time expects to be compensated for the time value of the money or for not using that money at the time of its loan. In addition, they will want to be compensated for the expected loss of purchasing power when repaying the loan. These expected losses include the possibility that the borrower will default or be unable to make payment on the terms originally agreed upon, or that the loan collateral will be less valuable than expected; the possibility of tax and regulatory changes that may prevent a lender from obtaining a loan or paying more taxes on the amount disbursed than originally anticipated; and loss of purchasing power relative to the money originally provided due to inflation.

Nominal interest rates

measure the amount of compensation for all three sources of loss plus the time value of the money itself.

Real interest rates

measure compensation for expected losses due to default and regulatory changes, and also measure the time value of money; they differ from nominal interest rates by eliminating the inflation compensation component.

Economy-wide, the "real interest rate" in an economy is often thought of as the rate of return on a risk-free investment, such as U.S. Treasury bills, minus an index of inflation, such as the rate of change in the CPI or the GDP deflator.

Fisher's equation

The relationship between real and nominal interest rates and the expected inflation rate is determined by the Fisher equation

1 + i = ( 1 + r ) ( 1 + π e ) { Displaystyle 1 + i = (1 + r) (1+ pi _{e})}

Where

i = nominal interest rate; r = real interest rate; π e { displaystyle pi _{e)) = expected inflation rate.

For example, if someone lends $1,000 for a year at 10% interest and receives back $1,100 at the end of the year, this represents a 10% increase in his purchasing power if the prices of the average goods and services he buys remain unchanged from with what they were at the beginning of the year. However, if the prices of food, clothing, housing and other things she wants to purchase increased by 25% during this period, she has actually lost about 15% of her purchasing power. (Note that the approximation here is a bit rough; since 1.1 / 1.25 = 0.88 = 1 – 0.88 = 0.12, the actual loss in purchasing power is exactly 12%.)

If the inflation rate and the nominal interest rate are relatively low, the Fisher equation can be approximated as follows:

r = i – π e . {displaystyle r=i-pi_{e}.}

Real interest rate after taxes

The real return actually received by the lender is lower if a non-zero tax rate is applied to interest income. Generally, taxes are levied on nominal interest earnings without adjustment for inflation. If the tax rate is denoted as t

, the nominal before-tax rate of return is

i

, the amount of taxes paid (per dollar or other unit invested) is

i × t

, and thus the after-tax nominal return is

i

× (1 –

t

). Therefore, the investor's expected real after-tax return using the simplified approximate Fisher equation above is given by

Expected real after-tax return = i ( 1 – t ) – π e . { displaystyle i (1-t) – pi _ {e}.}

Variations in inflation

The inflation rate will not be known in advance. People often base their expectations of future inflation on average past inflation rates, but this creates errors. The ex-post real interest rate may be very different from the ex-ante real interest rate that was expected in advance. Borrowers hope to repay cheaper money in the future, while lenders hope to get more expensive money. When lenders underestimate inflation and currency risks, their purchasing power will decline overall.

The complexity increases for bonds issued over a long term, where the average rate of inflation over the life of the loan may be subject to great uncertainty. In response, many governments have issued real yield bonds, also known as inflation index bonds, in which the principal value and coupon increase annually with the rate of inflation, bringing the bond's interest rate closer to the real rate. interest rate. (For example, a three-month delay in the indexation of TIPS could result in a deviation of up to 0.042% from the real interest rate, according to a study by Grishchenko and Huang.) Inflation-protected securities (TIPS) are issued in the United States. from the US Treasury.

The expected real interest rate can vary significantly from year to year. The real interest rate on short-term loans is highly dependent on the monetary policies of central banks. The real interest rate on long-term bonds tends to be largely determined by the market, and in recent decades, with the globalization of financial markets, real interest rates in industrialized countries have become increasingly correlated. Real interest rates have been low by historical standards since 2000 due to a combination of factors, including relatively weak demand for loans from corporations as well as strong savings in the newly industrializing economies of Asia. The latter offset the US federal government's large borrowing requirements, which would otherwise have put more pressure on real interest rates.

Related to this is the concept of “return on risk,” which is the rate of return minus risks measured relative to the safest (least risky) investment available. Thus, if a loan is made at 15% interest with an inflation rate of 5% and 10% risk of default or repayment problems, then the risk-adjusted rate of return on investment is 0%.

The real interest rate is...

A striking example of the Fisher effect, discussed in the previous chapter, is the picture when the expected rate of the inflation process is equal to one percent on an annual basis. Then the nominal interest rate will also increase by one percent. But the real percentage will remain unchanged. This proves that the real interest rate is the same as the nominal interest rate minus the expected or actual inflation rate. This rate is completely free of inflation.

Deposit protection

Deposits up to 1,400,000 rubles inclusive are protected by Art. 11 and part 7.2 of Art. 36 of the Federal Law of the Russian Federation “On insurance of deposits of individuals in banks of the Russian Federation”.

According to data from July 17, 2021, over 705 banks participate in the system of compulsory insurance of bank deposits of the population (CDI), of which 6 operate, but do not have the right to accept deposits from individuals.

Important: The size of the premium insurance rate is regulated by the state corporation “Deposit Insurance Agency”.

In this article we will look at the TOP 10 financial organizations offering favorable interest rates on deposits. The rating is formed according to data directly from official sources of banks.

Nominal interest rate

When we talk about lending rates, we usually talk about real rates (the real interest rate is the purchasing power of income). But the fact is that they cannot be observed directly. Thus, when concluding a loan agreement, an economic entity is provided with information about nominal interest rates.

The nominal interest rate should be understood as a practical characteristic of interest in quantitative terms, taking into account current prices. The loan is issued at this rate. It should be noted that it cannot be greater than zero or equal to it. The only exception is a loan on a free basis. Nominal interest rate is nothing more than interest expressed in monetary terms.

Why is everything so difficult

The situation with credit offers in Russia is already so confusing that you can go through a dozen articles, and it will still not be clear what to focus on and how much you will have to pay in the end. It is only clear that you will have to pay more.

When preparing this material, Financer.com experts looked through more than 20 financial resources and saw an interesting picture - “dictionary definitions” are given everywhere, but there are practically no explanations in human language.

Let's change this...

Calculation of the nominal interest rate

Suppose an annual loan of ten thousand monetary units pays 1,200 monetary units as interest. Then the nominal interest rate is equal to twelve percent per annum. After receiving 1200 monetary units on a loan, will the lender become rich? This question can be answered correctly only by knowing exactly how prices will change over the course of an annual period. Thus, with annual inflation equal to eight percent, the lender's income will increase by only four percent.

The nominal interest rate is calculated as follows: r = (1 + percentage of income received by the bank) * (1 + increase in inflation rate) – 1 or R = (1 + r) × (1 + a), where the main indicator is the nominal interest rate rate, the second is the real interest rate, and the third is the growth rate of the inflation rate in the country corresponding to the calculations.

Related terms

The base rate usually refers to the annual rate offered on deposits by a central bank or other monetary authority.

The APR and effective interest rate or equivalent annual rate are used to help consumers compare products with different payment structures on a general basis.

The discount rate is used to calculate the present value.

The coupon interest rate is the ratio of the annual coupon amount (the coupon is paid per year) to the face value, while the current yield is the ratio of the annual coupon divided by its current market price. The yield to maturity is the expected internal rate of return on a bond given that it is held to maturity, that is, the discount rate that equates all remaining cash flows to the investor (all remaining coupons and par value repayment at maturity) with the current market price.

conclusions

There is a close relationship between nominal and real interest rates, which for absolute understanding it is advisable to present as follows:

1 + nominal interest rate = (1 + real interest rate) * (price level at the end of the time period under consideration / price level at the beginning of the time period under consideration) or 1 + nominal interest rate = (1 + real interest rate) * (1 + rate inflationary processes).

It is important to note that the real effectiveness and efficiency of transactions performed by the investor is reflected only by the real interest rate. It talks about the increase in the purchasing power of the funds of a given economic entity. The nominal interest rate can only reflect the increase in funds in absolute terms. It does not take inflation into account. An increase in the real interest rate indicates an increase in the level of purchasing power of the monetary unit. And this equals the opportunity to increase consumption in future periods. This means that this situation can be interpreted as a reward for current savings.

The importance of economic theory

Effective federal funds rate and prescriptions from alternative versions of the Taylor rule

The amount of physical investment, particularly the purchase of new machinery and other productive facilities in which firms engage, depends on the level of real interest rates, since such purchases usually must be financed by issuing new bonds. If real interest rates are high, the cost of borrowing may exceed the real physical income from some potentially purchased machines (in the form of output); in this case, these cars will not be purchased. Lower real interest rates will make it profitable to borrow to finance the purchase of more cars.

The real interest rate is used in various economic theories to explain phenomena such as capital flight, business cycles, and economic bubbles. When the real interest rate is high due to high demand for credit, the use of income will, ceteris paribus, shift from consumption to savings, and physical investment will fall. Conversely, when the real interest rate is low, the use of income will shift from savings to consumption and physical investment will increase. Various economic theories, beginning with the work of Knut Wicksell, have explained the effects of rising and falling real interest rates in different ways. Thus, international capital moves to markets offering higher real interest rates from markets that offer low or negative real interest rates, causing speculation in stocks, real estate and exchange rates.

Real Federal Funds Rate

In setting monetary policy, the United States Federal Reserve (and other central banks) uses open market operations, influencing the volumes of very short-term funds (federal funds) supplied and demanded and thus influencing the federal funds rate. By targeting a low rate, they can stimulate borrowing and therefore economic activity; or vice versa, by raising the rate. Like any interest rate, there is a nominal and a real value, determined as described above. Additionally, there is a concept called the "equilibrium real federal funds rate" (r*, or "r-star"), also called the "natural rate of interest" or "neutral real rate", which is the "level of the real federal funds rate "if it is allowed to prevail for a few years, [it] will boost economic activity to its potential and keep inflation low and stable." Various methods are used to estimate this amount using tools such as Taylor's rule. This rate may be negative.

Notes[ | ]

- Interest Rate History Archived October 16, 2008 on the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-10-27

- UK interest rates decreased to 0.5%

- Homer, Sylla & Sylla, 1996, p. 509.

- Bundesbank. BBK - Statistics - Time series database Archived copy dated February 12, 2009 on the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-10-27

- Zimbabwe currency revised to help inflation (undefined)

(inaccessible link). Access date: October 31, 2011. Archived February 11, 2009. - Fixed interest rate (undefined)

(inaccessible link). National Economic Encyclopedia. Access date: July 16, 2013. Archived December 27, 2014. - Borisov A. B.

Floating interest rate // Big Economic Dictionary. - M.: Book World, 2003. - 895 p. — ISBN 5-8041-0049-1. - Borisov A. B.

Interest rate // Big economic dictionary. - M.: Book World, 2003. - 895 p. — ISBN 5-8041-0049-1. - Interest rate // Great Russian Encyclopedia: [in 35 volumes] / ch. ed. Yu. S. Osipov. — M.: Great Russian Encyclopedia, 2004—2017.

- Moiseev S. R.

Money with a negative interest rate // Money and Credit, 2017. - No. 10. - P. 16-26.